Sound Effects Guy: Don’t Call It Foley

August 23, 2013

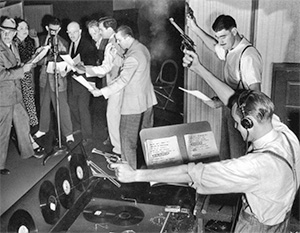

This weekend, MH's Mike Martini and Mark Magistrelli will be performing live sound effects on stage for a radio recreation of a script entitled The Canterville Ghost for a Cincinnati theater company. It's the sixth production for Martini producing the sounds of doors closing, footsteps, thunderclaps, horse clops, etc., for this theater company. Mike has been a bit of a “sound effects nut” over the last decade or so, studying techniques of the artists from radio's golden age and finding new “sounds” for modern ears. Just, please, don't call him a Foley Artist.

It's not that a true radio sound effects person has anything personal against a Foley Artist—indeed, on the surface they seem to do the same thing. And yet, not really. The original “Foley Artist” was none other than Jack Foley, himself; a sound technician from the silent film days of Universal Studios. When the “talkies” came about in the late 1920s, Foley struggled to have early film stars heard on film because of the primitive nature of carbon microphones and sound horns. So Foley devised a way to add or “augment” voices and sound effects synchronized to early sound-on-film. That his name has been immortalized for the process he invented is a tribute to his skill and creativity. Today's film Foley Artists work strictly during the post-production part of filmmaking. They still sometimes make sounds by hand but mostly those sounds are digitally pre-recorded in a huge sound board. Still, the all of the sounds are added “after the fact.” This allows a Foley Artist to “get it right” each and every time.

A “real” (read: radio) sound effects artist didn't have the luxury of post-production. They did it “live” alongside the actors. Although some effects were on prerecorded discs, they still had to be performed live. Like walking on a tightrope, it's that vulnerability, that possibility of a very audible mistake, that separates a sound effects artist from a Foley. And mistakes did happen, too—guns misfired, equipment broke, etc., but the sound effects artist was responsible for an important part of the broadcast. Just how big a part? A radio program without sound effects is like a painting without a canvas. It's the picture painted in the listener's imagination that gives the dialogue width, depth and breadth.

With the death of the golden age of radio, many sound effects artists probably became Foley Artists—however, if you ran into them in the studio commissary, my guess is they probably took umbrage to being called a “Foley.”

Read similar stories: Did You Know, Radio